Lean, Agile, Teal …… how does sociocracy fit in?

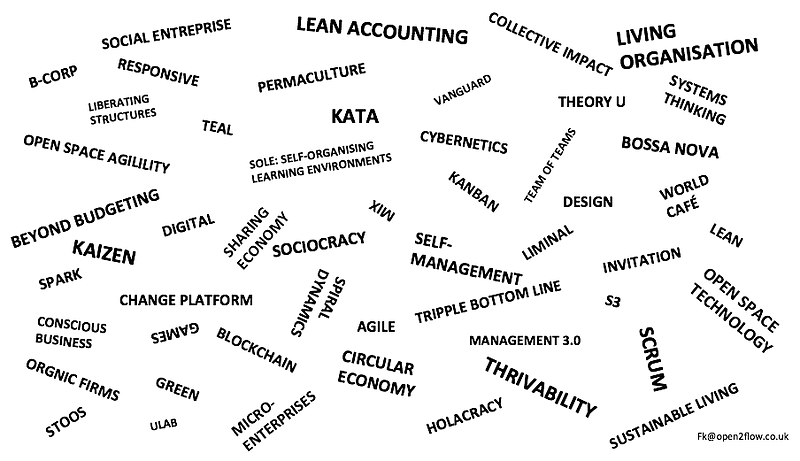

I’d like to explore the relationship between sociocracy and various other methods currently being discussed in the context of the future of organisations and of work. How does Sociocracy fit in with Lean, Teal, Agile, and all the many other recent movements? Where does Sociocracy sit?

I’ve been involved with Sociocracy for almost 10 years now, but I first came across it because I was looking for a solution to a problem in Lean, the Toyota production and management system. I learned Lean manufacturing in the automotive plants in Japan; and later back in the West I was looking for a way to introduce, as part of implementing Lean, the way the Japanese do participatory decision-making. Their way of empowering all staff members just wasn’t working here in the West, because it was culturally anchored, they did it naturally, so they had not developed a specific system as such for it, and I soon realized I needed an explicit approach, which had been developed in the West — that’s how I eventually came across Sociocracy. At the time to me Sociocracy was a Western piece of the much larger Lean production and management system, though it then became a passion in its own right.

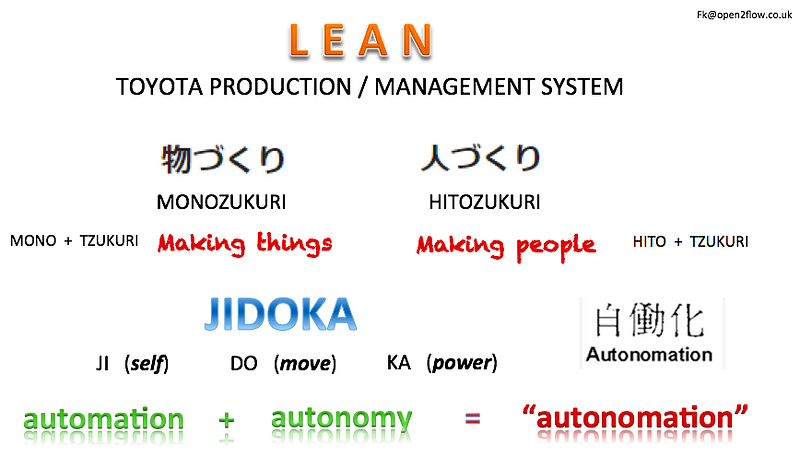

Taiichi Ohno, one of the founding fathers of the Toyota Production System, famously said Toyota were in 2 businesses, that of mono-zukuri and hito-zukuri, that is of making things (in this case cars) and in making people (that is developing people). One of the key principles of Lean is that of jidoka, which is a play of words (or kanji), ji meaning self, ka meaning power and doo meaning either move or manage, and jidoka translates as either automation (moving by itself) or (with a small twist in the kanji) autonomy (relying on self, independence), from which the unusual combined word ‘autonomation’ was created, i.e. both automatic and autonomous, but implicitly it is also self-managed and self-regenerative.

Coming back to the principle of making people, the whole purpose of that was to develop every-one right to the shop-floor, by giving them the right tools and information, such that they could operate automatically, without the need for commands from anyone, and autonomously, independently being able to make their own decisions, by themselves or as part of teams. In other words a major element of Lean operations is this whole emphasis on the human development side — and this, I should say, is the part that got lost in translation in the West.

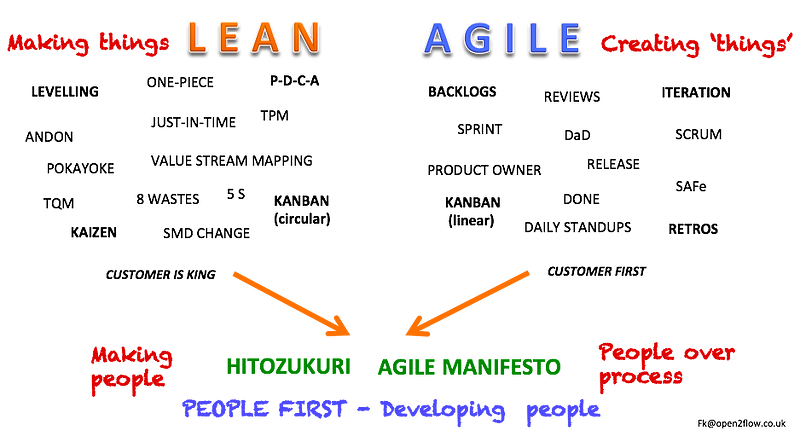

Of course there is a lot more to Lean, like Just-in-time, Kaizen, 5S, Pokayoke, TQC, Single Die change, Andon, One-piece production, TPM, Leveling, Stream mapping etc., but all of these are technical in nature, and only work well if shop-floor operators are fully engaged autonomously making their own decisions and quality feedback.

In the 1980’s Toyota were quite secretive about their approach, thinking the West would copy them and they would otherwise soon lose their competitive advantage. They needn’t have been. Twenty years later they openly published their “secrets” in a 14 point document, and the funny thing is, even today most Western companies still don’t get it! And that is because they focus on the mechanics while largely ignoring the other half, the human aspect that makes it work.

No doubt there have been many inroads applying Lean principles in the West, in and beyond manufacturing, indeed in hospitals, in the construction and transportation industries, to name a few. But there are some industries, where the technical aspects of Lean do not work, they do not apply. Specifically this is the case in the more creative and development industries; and indeed this is what gave rise to the Agile movement in IT and software development.

While Agile also has a technical side to it, expressed in Scrum, Product owners, Sprints, Reviews, SAFe, linear Kanban, DaD, Sprint Retros, Daily standups, Backlogs, etc., the essence of Agile is expressed in the Agile Manifesto, which is all about people before processes, customer satisfaction over profit and fundamentally putting the human aspect over the technical one. And that is fundamentally the same hitotzukuri (making people) aspect found in Lean; indeed that’s why Agile people often refer to the Lean heritage — sometimes thinking it is the same thing. In Agile the words Lean and Agile are used almost interchangeably, whereas in Lean that would be completely inconceivable; nevertheless the Agile Manifesto is where the two do join.

So while the mechanics of Lean and Agile are quite different, the fundamental emphasis on the human side is at the heart of both, as it is to many of the other movements mentioned, such as Conscious, Sharing economy, Circularity, Responsive, Sociocracy, Holacracy — they are all different in their own way, but what they have in common is this focus on the human side. And by that I don’t just mean people-centredness and humaneness, but also developing people in communities in such a way that the can grow, achieve their full potential, develop themselves and thereby contribute to the groups they are part of…. and where workplaces move from being places of drudgery, to places of collaborative growth, learning and development, and even of joy and living.

So why don’t Lean and Agile talk to each other? Well despite their being linked and of the same breed through the human development side of things, they don’t talk to each other, in the same way production people rarely talk to IT people, and for the same reason siloed finance people don’t talk to siloed marketing people, i.e. in our world of specialization and fragmentation they fundamentally do not understand each other. So the revolutionaries amongst the finance people have independently come up with their own version of human development, in the 12 principles of Beyond Budgeting. Which is absolutely great, but in the end they are ‘local’ or functional variations of the same fundamental theme, that of putting people first and making workplaces, amongst other things, a place of joy and learning.

So what about Sociocracy? Well, technically it’s about governance, collective decision-making and distributed leadership, and actually complements many of the other movements. However, fundamentally the same principle applies: putting people first, all people, with a way that enables everyone’s voice to be heard and respected in the particular context that affects them. It’s about people and community development.

All these methods are technically different, and we argue about these differences. Though I see them more as complementing each other, they are also of the same blood philosophically, that is around humans and learning. They all point to a beautiful vision for the future of work, if indeed we ever make the transition (because current mainstream reality is quite different), that of organisations and workplaces being places of self actualization and growth.

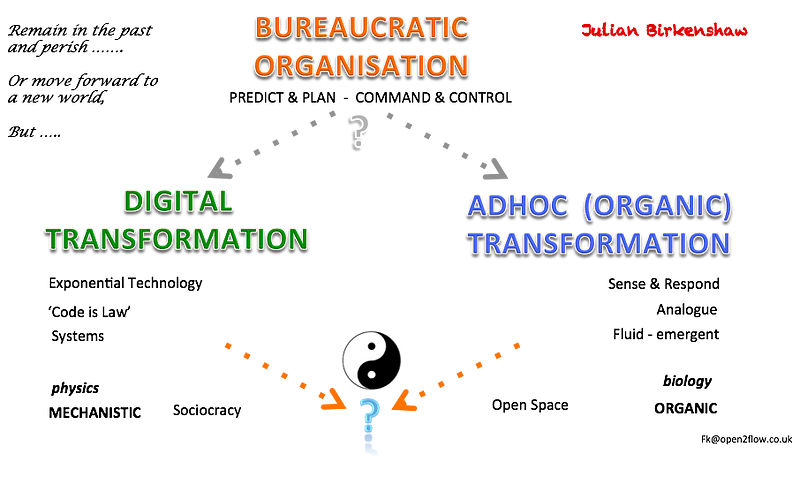

But I’d like to throw a spanner in the works, something that I was made aware of by London Business School professor and Gary Hamel collaborator, Julian Birkenshaw, who has basically said there is not one choice into the future, i.e. being stuck in past ways of command and control bureaucracy, or of moving forward to new forms, but there are actually two incompatible trends into the future; one he refers to as the Digital transformation process, and the other as what he calls the ‘Adhoc’ transformation, named so because it is unpredictable, fluid, learning by trying, emergent and unmanaged, what I would prefer to call organic (organic because it is based on living and biology, self-regenerating, holistic). He says that while both are alternatives to the current bureaucratic command and control approach, the two are actually going in opposite directions.

By definition digital relies more and more on being able to decode all aspects of the world, of business, of operations etc down to a basic level of 1 and zero — and when you think about it it’s the ultimate in mechanistic thinking. And this is almost the opposite of analogue, organic emergent thinking.

When seen from this vantage point, Sociocracy appears quite mechanistic. The first key statement of the sociocratic norms states that its purpose is to demonstrate equivalence in decision-making. In other words the strict one-by-one rounds in strict sequence of clarifying-reacting-consenting are there to demonstrate clearly that everyone was able to put equal value in the collective decisions, a quite mechanistic process, in the same way that counting votes is mechanistic in democratic elections.

And this mechanistic nature has always troubled me as a Sociocrat, because I have an inclination towards the organic, regenerative aliveness of things, fluid, unpredictable and imperfect as that may be; and so in my own practice I’ve always counter-balanced Sociocracy with Open Space technology, which is more self-organising, organic and magical or alive. Both aim for similar human-centred things, but one is more mechanistic the other more organic in nature.

So as a consequence I increasingly see Sociocracy not as a goal but a means. In the early days I used to ask myself how can we make organisations more sociocratic, how do we transform them to be sociocratic, as if Sociocracy was the goal. Nowadays I see this question rather irrelevant, after all, the goal should be creating workplaces of joy and self-development. Rather I now see Sociocracy, as well as Lean, Agile, Beyond Budgeting etc. as different means and training grounds for getting there.

Because Sociocracy grew out of traditional company structures to begin with, its practices might be excellent learning platforms to help organisations transform from their current plan and control, hierarchical and bureaucratic modus operandi towards self-organised organic entities — by giving people tools to change habits, initially by mechanistically going through all the motions that will over time put people in a different mindset with new habits. And this is precisely what Toyota and others did in the 1960s to 80s, when they retrained their whole management staff from being commanders to being coaches and stewards nurturing their teams. The principle is called Kata. Kata are mechanistic practice steps, like little workouts, a few steps at a time, as when learning to dance, which help people change habits or learn new patterns.

So in this view the principles and key practices of Sociocracy could become learning Kata which could enable organisations to transform to a more what could be called Teal mind-set, where self-management and autonomy, where holistic integral thinking and whole person thinking, and where emergent, organic development and purpose are the rule. Personally I prefer Sociocracy because of its fundamental simplicity, just four principles, and it works as an empty vessel, that is it can integrate well with any other tool or approach. And digitalization need not be a different futuristic path of being ruled merely by coding, as Birkenshaw suggested, but could, ironically, provide Kata steps to help us move from a mechanistic mindset to a more organic and emergent one.

Finally I should say, we often speak of these approaches as if they were the panacea of the future, we guard them fervently against other similar approaches. There was an attempt in 2012 to try to bring these various approaches together in order to achieve more collective impact, resulting in Stoos and Spark, but this was then drowned out by Teal, and no doubt something else will soon come along.

However, I don’t think that our goal should be a grand unified organic theory of the future, but on the contrary I take comfort in the diversity of ideas, methods and approaches, and rather than taking an Either/Or perspective, that is either Agile or Lean, either Sociocracy or Holacracy, either Responsive or Conscious and so on, we take a Both/And Complementary point of view, all helping us maintain a balanced diet of methodological ingredients.

I therefore invite all of us to embrace this diversity of ideas and celebrate complementarity, with a view of making our organisations of the future human places of collaboration, of learning and ultimately of joy and achievement in the workplace.