| |

Why aren't Lean and Agile collaborating?

Debunking the myth that Lean and Agile are the same

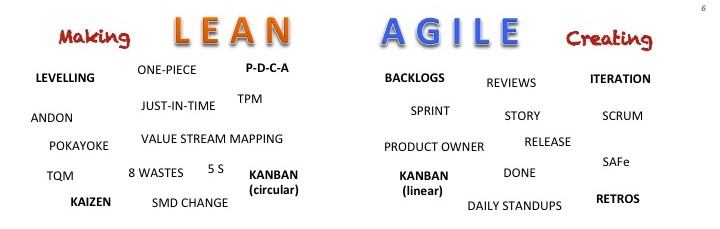

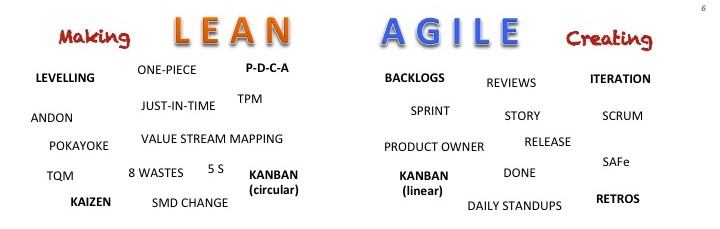

To the Agile community this question may seem strange. Many Agile practitioners regard ‘Lean’ and ‘Agile’ as almost synonymous. Yet if Agile people were to move away from their screens into the Gemba world of Levelling, Value Stream Mapping, PDCA Problem-solving, 5S and Andon, then it is hard to believe they would still be saying that Sprints, Scrum, Backlogs, Retro reviews and Done are the same thing. Nothing could appear more different.

Of course this depends on which definition of Lean you take. I use ‘Lean’ as first described by Womack, Jones & Roos in The Machine that changed the World in 1990 to denote the Toyota production and management system. The original advocates of TPS wanted to de-contextualize it from Toyota, to capture its generic principles applicable beyond cars, beyond manufacturing, and so gave it the term ‘Lean’ at the time; sometimes to their regret, as the term has created as many problems as it has solved; the term has mislead many along unintended paths (e.g. Six Sigma), or it has been misappropriated for almost opposite intentions (e.g. as in 'lean and mean').

So why are Lean and Agile not talking to each other? The Agile and Lean communities appear to have quite different personalities. Agile are very active, with an open source orientation, more inclined to share, as is evident on the hundreds of meet-ups and conferences. On the other hand Lean advocates tend to be more secretive, appearing more distanced, with comparatively little in terms of sharing, except with the already initiated. Lean sometimes comes across as an old-schoolboy network, with an engineering penchant, despite it operating in a very hands-on Gemba environment. As a result of it being more publicly active, Agile has thus spread much more quickly within organisations, and appears to have a stronger hand in terms of appreciation in the business community.

PRESENTATION GIVEN AT ONLINE INTERNATIONAL SOCIOCRACY CONFERENCE ON 1ST MAY 2018

I’d like to explore the relationship between sociocracy and various other methods currently being discussed in the context of the future of organisations and of work. How does Sociocracy fit in with Lean, Teal, Agile, and all the many other recent movements? Where does Sociocracy sit?

I’ve been involved with Sociocracy for almost 10 years now, but I first came across it because I was looking for a solution to a problem in Lean, the Toyota production and management system. I learned Lean manufacturing in the automotive plants in Japan; and later back in the West I was looking for a way to introduce, as part of implementing Lean, the way the Japanese do participatory decision-making. Their way of empowering all staff members just wasn’t working here in the West, because it was culturally anchored, they did it naturally, so they had not developed a specific system as such for it, and I soon realized I needed an explicit approach, which had been developed in the West — that’s how I eventually came across Sociocracy. At the time to me Sociocracy was a Western piece of the much larger Lean production and management system, though it then became a passion in its own right.

A DEEPER DEMOCRACY FOR SCOTLAND?

October 2013 François Knuchel

Article submitted to Common Weal exploring referendum

The Common Weal has identified six transitions required to move towards its vision for Scotland. If I were asked which one of them to start with, I would begin with the last one – Democracy and Governance. The first five are about policy, but the sixth is about process, and most importantly it is about getting the whole Scottish population behind a vision. This is the participatory democracy it seeks. If there are lessons to be learned from the separatist movement of Quebec in Canada, for instance, it is that a democratic process must underpin independence, one which allows all voices to be heard. What strikes me about the Common Weal transitions is that the first five seem political in nature; not all in Scotland may necessarily agree with them; whereas democratisation is about ensuring all those views are heard, respected and considered.

But what exactly does it mean to have a participatory democracy? Participation in what and how? What is a "deeper democracy"? Allow me to muse about these questions, let me trot around the world, including back in history, and ponder how democracy and participatory leadership have been practiced in different ways here and there, in civic life as well as in business and communities. I shall first look at different shades of democracy or participatory governance in both business and governments and then explore newer and "deeper" forms of democracy for the future, including a true gem – dynamic self governance.

COMMUNICATION BOTTLENECKS

What are the Key Barriers to Effective Cooperation within Organisations – and how to overcome them

François Knuchel

Introduction:

Are you a director, manager or executive frustrated by unnecessary conflict and hurdles to effective cooperation in your organisation? Are you looking for inspiration to break through communication barriers? Do you simply want to create a team spirit across your organisation? If so, then you may find a few useful tips here. As our organisations become flatter and rely more and more on cooperation, new leaders are required who can inspire empowered cooperation, and who can therefore communicate at all levels.

Because of major restructurings, such as reorganisations, downsizing, mergers, joint ventures, or alliances, many organisations find that their people are not working coherently together. They are losing clients, losing key talent or failing to sustain competitive advantage, due to poor cross-functional communications, internal conflicts, misunderstandings and stress, or because of poor working relations across borders. Increasingly productivity demands require smoother operational workflow, so organisations have to work harmoniously together, only achievable through proper communication flow.

So what hampers communication flow? Here I look at some of the bottlenecks or hurdles that can cause poor collaboration. I also look at how organisations can generate greater cooperation and innovation across boundaries, and thereby raise productivity. Some of the benefits include reduced talent attrition, improved customer satisfaction and leverage from a diverse workforce. Here I explore:

- 10 communication pitfalls in pan-organisational cooperation

- 5 solutions: competencies or virtues to be promoted

- An overview of international communication

REFLECTIONS ON THE SUZUKI - GM CAMI PROJECT

What have we learned from the Suzuki0-GM CAMI technology transfer project in the late 1980s? * Here is a potpourri of personal reflections on the preliminary trainer-training I project-managed in Japan, seen in terms of intercultural communication and training issues.

Francois Knuchel, 2000

The Fluidity of Culture

During the CAMI TPS (Toyota Production System) transplant at Suzuki, similarly also at Toyota, Nissan & Honda, there was a vigorous debate amongst practitioners and academics as to what elements of TPS were culturally predetermined? In other words which features of TPS were practiced in Japan simply because they were part of Japanese culture and which elements were "invented" for the purpose of a more efficient manufacturing process, and were therefore more easily transferable to other parts of the world.

It was deemed that the "cultural elements" would not be transferable. Therefore Suzuki should only attempt to transfer the "invented" culture-free parts of the system. Teamwork, Teian and Kaizen, for example, were initially considered to be cultural, because they are based on collectivist consensus driven process, and would thus not be accepted or adopted easily in the West. Many Westerners took the view that if something was culturally determined there was not much point trying to transfer the concept. By contrast many Japanese took the view that by empowering the local workforce with trust and dignity they could more easily introduce newer different approaches, however alien they may seem to Western management.

LEAN PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

SUZUKI / GENERAL MOTORS CAMI PROJECT

This is my personal account of the CAMI technology transfer project of intercultural and training issues in aspects of project-managing the preliminary trainer-training in Japan in the late 1980s.

Francois Knuchel, 1989

CAMI Technology Transfer Project

Rationale for Suzuki Approach & Overview of Trainer Training

In the late 1980's General Motors and Suzuki set up a joint venture in Canada, CAMI. It was a green-field automotive plant to manufacture the Cultus/Swift and Samurai/Vitara cars using lean Japanese manufacturing principles, the so-called Toyota Production System, involving a massive transfer of lean manufacturing principles and know-how from Japan to North America. I was in charge of the preliminary communications (language, presentationa and cross-cultural) and trainer training program of 180 selected Japanese "trainers", from plant manager to shop floor supervisors, designed to enable them to "transfer" their know-how to 2,000 'associates' in the new CAMI Ingersoll plant in Canada.

This is a brief personal account on how we managed the training program. The details of the CAMI project are described elsewhere (pdf file). What I want to describe here is a little about the training program itself, and some of the considerations that lead to the kind of training programme we did in the first place. This project is of interest from both an industrial practice perspective as well as from an intercultural point of view.

-

You are here:

-

Home

-

Articles

|